What is a rhetorical device?

A rhetorical device, sometimes called a ‘figure of speech’, a persuasive device or rhetoric, is a linguistic tool that can be used to evoke a particular reaction from the reader or listener.

There are many types of rhetorical devices that can be used in either writing or spoken communication. If a device is only used in writing, it’s sometimes referred to as a literary device.

Chiasmus: definition

Chiasmus (pronounced kee-az-muss) can be likened to a grammatical mirror: it’s the reversed repetition of the grammatical structure of a phrase or sentence. Unlike other rhetorical devices that include repetition, such as epistrophe and anaphora, chiasmus only has to repeat the structure, not necessarily the words. Although the term ‘chiasmus’ might not be familiar to you, you've probably come across plenty of examples. Chiasmus is often used in literature, song lyrics, performance, speeches and advertising to create emphasis and rhythm. You can find examples almost everywhere, from William Shakespeare’s work to JFK’s speeches and even everyday idioms.

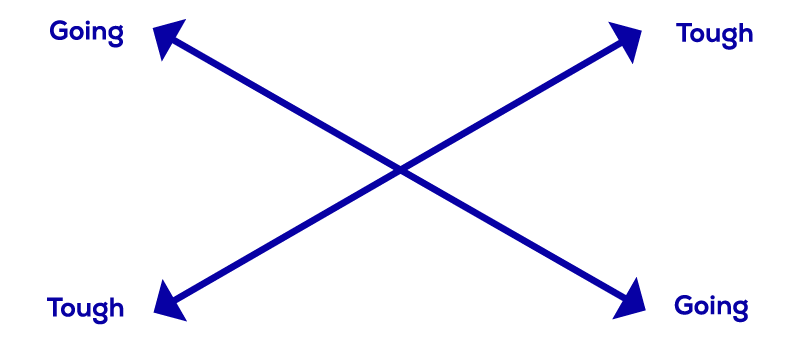

Perhaps you’re familiar with the expression, ‘When the going gets tough, the tough get going’? This is an example of chiasmus, as ‘going’ and ’tough’ swap places in the second clause. You might notice that the reversal is shaped according to an ABBA pattern. This is where the rhetorical device’s name comes from – the reversal creates a kind of X, which is the letter it’s named after (‘chi’ in Ancient Greek).

As a rhetorical device, chiasmus usually takes the form of a sentence or phrase as described above. But it is sometimes applied more broadly and metaphorically to describe inversion in whole passages, plots or even sounds.

There are many types of literary techniques used to create various effects. Although chiasmus isn’t as commonly used as some of the other rhetorical devices covered in this series, it’s a powerful one. If you want to improve your writing or verbal communication skills, a good working knowledge of rhetorical devices such as chiasmus can be a great help.

The purpose of chiasmus

Chiasmus can be used to present a concept and then to deepen or elaborate that concept in subsequent clauses. This is a very persuasive tool and can keep an audience, whether they are reading or listening, engaged with the content. It can also be used to break up complex concepts into bite-sized chunks, using clever structure to emphasise and deepen the connections between each section.

When chiasmus is used well, it can add a pleasing rhythm and verbal harmony to text that gives it an almost musical quality. That having been said, when chiasmus is used by a writer without skill, it can sound old-fashioned and clumsy.

The effect that any rhetorical device has is purely subjective. It relies on the interplay between the writer and the audience. A skilled writer will know their intended audience and have an idea of their likes and dislikes, their societal ideas and preferences. This means that the right rhetorical devices can be chosen to create the desired effect.

What are the rules?

To qualify as chiasmus, symmetry must be apparent in the repeated structures. The clauses themselves need not be symmetrical though. For example, the second clause in a two-part chiasmus might be longer than the first. However, it will mirror the first clause and the concepts in each clause will be connected.

The connection required between the clauses is flexible. The concepts might be directly linked or could be a comparison or juxtaposition. You don’t even need to use the same wording in both phrases to create chiasmus.

For example, if we were to describe Batman’s identity using chiasmus, we might say: ‘A billionaire by day, by night a superhero.’

One reason that chiasmus isn’t a more commonly used rhetorical device is that the inverted grammatical structure can make the phrase sound awkward. When used well it is good; but good it is not when used badly – did you see what we (awkwardly) did there?

Let’s have a look at examples of chiasmus.

Chiasmus examples in literature and poetry

Literature

Many skilled writers, both modern and historical, have used chiasmus well.

For example, ‘The instinct of a man is to pursue everything that flies from him, and to fly from all that pursues him.’ – Voltaire.

This memorable piece of writing is made powerful by the opposition between the clauses, which is contrasted by the reversal in structure.

Here’s another example that uses a similar technique to create opposing clauses that are contrasted by the reversal: ‘You forget what you want to remember, and you remember what you want to forget.’ – The Road by Cormac McCarthy.

Poetry

Chiasmus creates great rhythm in writing and is a useful tool in persuasive rhetoric that aims to focus attention. That’s why it’s more common in poetry than many other forms of writing. Many well-known poets, both modern and historical, have used chiasmus to create literary magic.

For example, ‘The mind is its own place, and in itself can make a heaven of hell or a hell of heaven.’ – Paradise Lost by John Milton.

The chiasmus here is created by the ‘make a heaven of hell or a hell of heaven’ part of the phrase. Notice how Milton creates opposing parallel concepts. The technique creates a memorable rhythm and deepens the idea through contrast, which makes this a very powerful part of the poem.

If the concepts are similar rather than contrasting, chiasmus creates emphasis.

For men diseased; but I, my mistress’ thrall, /Came there for cure and this by that I prove, / Love’s fire heats water, water cools not love. – Sonnet 154 by William Shakespeare.

In this example, both parts of the phrase have similar meanings. The second clause, ‘ water cools not love’ almost repeats the meaning of the first clause, but reverses the concept, which creates emphasis.

Chiasmus examples in speech and performance

Speech

People who deliver speeches that are intended to convince or influence an audience often use rhetorical devices to create impact. Chiasmus creates memorable structures, whether we read or hear them. It’s no accident that some of the best orators are also skilled in the use of chiasmus.

For example, ‘Ask not what your country can do for you – ask what you can do for your country.’ –John F. Kennedy.

This part of Kennedy’s speech is memorable thanks to the rhythm created by reversed structure and the juxtaposed concepts in the two clauses, which deepen the concept.

Using chiasmus in influencing and marketing

Carefully chosen words and clever literary devices get marketers good results. Successful adverts are often memorable, concise and designed to deliver their message with a punch. Chiasmus gives phrases an appealing rhythm and helps to create adverts that stick in our heads far beyond the timescale of their broadcasting campaign. They also provide the perfect structure for creating effective taglines.

Take a look at these examples:

- ‘There's no question Grape-Nuts is right for you. The question is, are you right for Grape-Nuts?’ – Grape-Nuts cereal, advertising campaign (c.1984)

- ‘Stops static before static stops you.’ – Bounce fabric softener advertising campaign (c.1990)

- ‘The economy of luxury, the luxury of economy.’ – Buget Car Rentals tagline

Antimetabole vs chiasmus

Antimetabole and chiasmus are sometimes confused, and scholars don’t always distinguish between the two. However, an antimetabole is generally seen as a type of chiasmus. Based on this categorisation, every antimetabole is a chiasmus, but not every chiasmus is an antimetabole.

How does that work?

The general rule is quite simple. Remember we said that chiasmus reverses the grammatical structure of a phrase in the second clause? The difference is that an antimetabole reverses the exact same wording in each clause.

For example, JFK’s line, ‘Ask not what your country can do for you – ask what you can do for your country’ while indeed being chiasmus, is also an example of antimetabole.

However, ‘A billionaire by day, by night a superhero’ is chiasmus but not antimetabole.

That’s the important difference between antimetabole and chiasmus.

Chiasmus and antithesis

Also sometimes confused with chiasmus is antithesis. Again, the two rhetorical devices are subtly different.

The word ‘antithesis’ means ‘this is the direct opposite’. Antithesis is another useful rhetorical device to have in your writing toolkit. It creates impact by placing opposing words or concepts parallel to each other.

For example:

‘That's one small step for man, one giant leap for mankind.’ – Neil Armstrong

Other rhetorical devices that use repetition

Epistrophe – the repetition of words, or words with a slight variation, at the end of successive clauses or phrases. Epistrophe is also known as epiphora or antistrophe. For example, ‘Last week, I was fine. Today, I am fine. Next week, I will be fine.’

Anaphora – the repetition of words at the beginning of

successive phrases. For example, ‘I will not fail. I will not falter. I

will not stop. And I will not give up.’

Alliteration – the repetition of the same consonant sound throughout a phrase. For example, the children’s nursery rhyme ‘She sells seashells on the seashore’.

Learn more about rhetorical devices and how to use them to improve your writing and communication in our list of literary devices.

Semantix creative copywriting

Semantix provides a full range of multilingual copywriting services. We pair you with a copywriter who has specific knowledge and experience in your industry. This means that you’re working with someone who understands your business needs and the language of your target audience.

Using rhetorical devices such as chiasmus works in every language but requires more skill than direct translation. When you’re writing creative marketing material, just substituting a word for one that means the same in another language often results in text that doesn’t make sense or fails to hit the mark. That’s why you need to work with a native-speaking copywriter. Our copywriters use rhetorical devices, among other language tools, to get clients the best results from their marketing material in over 200 languages.